A Letter from Ofer Military Court

by Gerard Horton of Military Court Watch

Note: The visit to Ofer military court described below occurred prior to COVID-19 restrictions.

There is nowhere to shelter from the elements as we wait patiently for the security gate to open at Ofer military court near Jerusalem. Separating us from an adjacent enclosure is a chain wire fence beyond which are jammed Palestinian families waiting to be processed through a series of security checks so they can attend a brief court appearance of a loved one. It is still early but the journey for these families is already hours old and most look tired and resigned to waiting many hours more in this grim place.

After a short wait, our group passes through security. Before leaving this area, an official in uniform hands us a seven-page document prepared by the Military Courts Unit explaining the legality of the facility we are entering. We continue on our way, winding along a wire-enclosed passageway until we arrive at a larger waiting area with a kiosk and a stinking toilet block. Although still crowded, this place has a calmer, although still anxious, atmosphere.

Before we enter one of the prefabricated shacks that serve as military courts, we talk to waiting families. In no time we are circled by anxious mothers, fathers, wives, brothers and sisters, sons and daughters, all eager to share their experiences. One after another, we hear of front doors broken down, soldiers shouting, children crying, rooms searched, and property damaged or removed. And always there are arrests – most without explanation or documentation. Some of these arrests occurred just days before, in towns and villages up and down the West Bank, from Jenin to Hebron. In other cases, the trip here has become a regular pilgrimage, the arrest having taken place months earlier.

For some, this was nothing new, part of a collective Palestinian experience repeated over and over since June 1967. For others, this was the first time the military had raided their homes and detained a loved one. A clear demarcation line soon appeared between the “old hands” and those for whom these experiences were new. One anxious young woman, recently married, described how her husband had been dragged away at 2:00 a.m. Although clearly worried, she expressed confidence that this was all just a terrible mistake, as he had done nothing wrong and was sure to be released today – inshallah. Her optimism produced wry smiles among the “old hands,” who knew from experience that few leave this place expeditiously – whatever they may or may not have done.

As we were waiting to enter a courtroom, I started to read the Military Courts Unit document. What is striking about it is the confidence with which it proclaims that “the Military Courts in Judea and Samaria [sic] were established in accordance with international law,” followed by a reference to the Fourth Geneva Convention. What is surprising is not the legal reasoning, which cannot be faulted, but the fact that this official Israeli document relies on the Fourth Geneva Convention to justify prosecuting Palestinian civilians in military courts while Israel rejects the application of the Convention to the issue of settlements. It is hard to imagine a more blatant attempt at legal cherry-picking.

A few weeks earlier in a village north of Ramallah, Israeli soldiers bang on a front door at 3:00 a.m. The father quickly runs to open up, knowing from experience that any delay is likely to result in the door being kicked in or destroyed. Ten soldiers enter the home and at gunpoint order all family members out of bed and into the living room. A young officer checks ID cards against a list of names given to him by an intelligence officer. A match is found and a 15-year-old youth is taken outside, tied, and blindfolded. Little information is provided before the youth is taken away to an interrogation center for questioning and likely prosecution at Ofer military court.

Frequently the charge is stone throwing or attending an illegal gathering, though sometimes it is more serious. Stories similar to this one have been playing out every night in the West Bank for over 50 years, with UN estimates suggesting that over 800,000 Palestinians have been imprisoned, of whom about 4 percent (32,000) were children.

Evidence collected by Military Court Watch (MCW) indicates that the overwhelming majority of arrests in the West Bank occur within a few kilometers of a settlement or a road used by settlers. This is no coincidence. To understand the link, one needs to understand the mission the military has been given by Israel’s political leaders since settlements started popping up in the West Bank in September 1967, namely: To guarantee the protection of the now nearly 460,000 Israeli civilians who have been encouraged to move across the Green Line in violation of international law to live among nearly three million Palestinians. No one should underestimate the challenge that such a mission presents.

Given these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that there are acts of violence against settlers in the West Bank from time to time. More surprising is that these acts of violence are relatively rare: The data show that 5.4 West Bank settlers have been killed per year over the last 10 years – a fatality rate of just 0.0013 percent per annum. Without trivializing these killings, the U.S. State Department has noted that the Israeli military was so successful in its mission in 2012 that not even one settler was killed that year in the West Bank.

What’s the secret? Well, just the skillful implementation and refinement of tried and tested tactics. The key tactical elements involve a combination of intimidation and collective punishment directed toward Palestinian communities who have the misfortune to live in close proximity to a settlement or supporting road network – the inevitable friction points. To understand how this system works, it helps to put yourself in the shoes of an Israeli military commander, remembering that your job is to ensure that Palestinians living close to a settlement understand that no form of resistance will be tolerated. Sounds easy enough, but it does present certain challenges.

One day you, the commander, are informed of a stone-throwing incident on a road near a settlement. There is no doubt that Palestinians are involved, as the intended target were Israelis – but there is little further information to help you identify the perpetrators. This poses a dilemma: An act of resistance has been perpetrated, but no perpetrator can be specifically identified. But if no one is punished, so the thinking goes, resistance will escalate, placing the viability of the settlement project in jeopardy – something that cannot be permitted.

To overcome the deficiency in evidence, the commander generally makes two assumptions that, from a military perspective, are probably reasonable. The first is that the stone throwers were Palestinian males aged between twelve and thirty; and the second, that they most likely came from the nearest village. And so it is towards that village that the commander turns his attention.

At this stage, the commander will generally call upon the services of an Israeli intelligence officer assigned to the area. Needless to say, after fifty-three years of military occupation, a large amount of intelligence has been collected on Palestinians throughout the West Bank, and particularly those living at these friction points.

The intelligence officer responsible for the village will review the files and ask some simple questions: who are the troublemakers; who has been detained before; and, most importantly, what do the informants in the village have to say? While definitive information on collaboration with Israel’s military is not easy to come by, anecdotal evidence suggests many thousands pass along snippets of information in return for small favors. Interrogation rooms are a popular recruiting ground; the methods used involve a careful balance between threats and inducements. Requests for permits and medical treatment also prove fruitful areas of leverage for any would-be recruiter.

The importance of Palestinian informants in maintaining control over the West Bank should not be underestimated. It works on two levels. First, informants ensure a constant flow of information, some accurate, some less so. The second, and by far the most important benefit of any recruitment system, is that the target community knows it has been infiltrated. Such knowledge has a profound psychological impact and undermines trust and confidence within the community, thereby degrading its ability to establish any systematic or coherent form of resistance – be that peaceful, political, or violent.

And so the intelligence officer prepares a list of names for the commander to arrest. The first round of arrests generally take place within 48 hours of the stone-throwing incident so that the village understands cause and effect: any act of resistance, large or small, will result in an immediate and overwhelming response by the military until resistance ceases. The military tries to make the arrests at night. First, because a suspect is more likely to be home at 2:00 a.m. Second, because street protests in response to the arrest are less likely at night. And third, night raids are an effective way to terrify the residents of the village into submission.

According to a recent report, Israel’s military conducts around 3,200 search–and-arrest operations in Palestinian communities in the West Bank each year. Approximately 2,800 of these occur at night, and in about 580 of these cases, a child is detained. By extrapolation, this would suggest over 148,000 nighttime search-and-arrest operations since 1967. This data paints a stark picture of constant military harassment to ensure that Palestinians never feel safe or secure, even in their own homes. In turn, this sense of insecurity inhibits the development of an effective counter-strategy.

The link between settlements and the intimidation of the Palestinian civilian population was succinctly described by a former Israeli soldier in a testimony provided to Breaking the Silence:

“A patrol goes in . . . and raises hell inside the villages. A whole company may be sent in . . . provoking riots, provoking children. The commander . . . wants more and more friction, just to grind the population, make their lives more and more miserable, and to discourage them from throwing stones, to not even think about throwing stones at the main road. Not to mention Molotov cocktails and other things. Practically speaking, it worked. The population was so scared that they shut themselves in. They hardly came out.”

And so the mission is accomplished. A population that is too scared to come out of their homes is hardly likely to present any serious opposition to the continued presence of settlements in occupied territory.

Back to the arrest operation: After being taken outside, tied, and blindfolded, the fifteen-year-old youth is led to a waiting military vehicle and taken away for questioning. Many detainees, including children, report being placed on the metal floor of military vehicles due to a lack of seats for both soldiers and detainees. Once on the floor of the vehicle, a detainee can expect some pushing and shoving, producing discomfort and sometimes worse. If a soldier or settler was recently killed or injured, the detainee can anticipate the treatment to be significantly more robust.

The journey to interrogation is rarely direct. The first stop may be a small settlement or military base somewhere in the West Bank, where the detainees are placed in shipping containers or left outside – generally still tied and blindfolded. Sleep is usually not an option and the provision of food, water, or toilet breaks unlikely, though this is largely dependent on the mood and disposition of the guarding soldier – something that can vary significantly from one unit to another.

At around 7:00 a.m., the detainee – sleep deprived, hungry, and possibly bruised and battered – will be bundled back into a military vehicle and delivered to an Israeli police station inside one of the larger settlements for interrogation. If the accusation is more serious, the detainee is likely to be transferred to Israel and handed over to the Shin Bet security service for a more thorough interrogation.

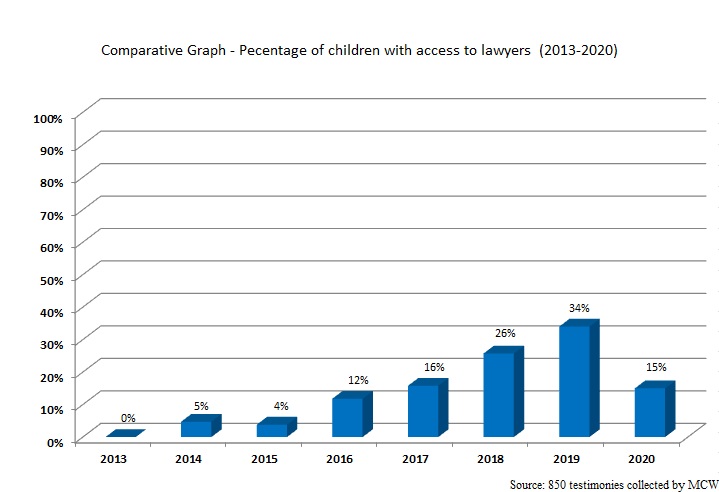

Under Israeli military law, an accused person enjoys the right to silence and must be informed of the right to consult with a lawyer upon arrival at a police station. But few detainees are informed of these rights or allowed to exercise them freely, and most ultimately sign a written statement transcribed in Hebrew by the interrogator, without knowing for sure what they have signed. During questioning, the detainee will almost certainly be told that the other detainees have all provided confessions and been released. The detainee, or his or her family, may also be threatened and the questioning will almost certainly be intimidating and sometimes physically abusive. Attempts may also be made to recruit the detainee as an informant with promises of early release, work permits, and other perks, or threats of violence and/or revocation of permits. Within a matter of days, the detainee will find himself in Ofer military court or its northern counterpart, near Jenin.

After listening to more stories at Ofer, all of which bear witness to the systematic nature of the military’s control in the West Bank, we made our way through one final turnstile to the courtrooms. Family members are not permitted in this area until their case is called, but as observers we are free to walk in and out, except for the court reserved for administrative detention reviews, where secret evidence is considered in private without being viewed even by defense lawyers.

Once through the turnstile, we make our way to the back of Court No. 7 – the remand court – which is also the busiest. The remand court is like a conveyor belt, with the accused shuffling through in batches of four – legs shackled. This is the same whether the accused is an adult or a child of twelve years old – the minimum age of criminal responsibility in the military courts. We sit and observe.

One of the first things you notice as you enter Court No. 7 is how crowded and chaotic it is. At one end you have the uniformed Israeli officials – the military judge, his or her assistant, a transcript typist, a translator, a prosecutor, and several guards. There are four or so detainees in brown prison uniforms, shackled and sitting in the dock. Then there are the lawyers, mostly Palestinian, some representing clients in the dock, others waiting around for clients to arrive. And finally, at the very back of the court, are the families, sharing fragments of information from the village with loved ones in the dock.

Apart from the surprising level of camaraderie between the Palestinian lawyers and the Israeli military court staff – built up, no doubt, from years of sharing this confined space – everyone else remains strictly within their own ethnic sphere. The Israeli military staff have their administrative duties to attend to, while for the Palestinians this is purely a family visit.

Rarely do lawyers run full evidentiary hearings, as the overwhelming majority of cases are concluded via plea bargain, whether or not the accused maintains his innocence or the evidence is credible. This is because release on bail is unlikely, which means it is generally quicker to accept a plea bargain than to wait in prison on remand for a judge to hear the case. Not surprisingly, few Palestinian detainees have much confidence that they would receive a fair hearing even if they rejected a plea bargain – partly because the judges are Israeli military officers and partly because some judges live in the settlements. Statistically, the odds are firmly against an acquittal, with the official conviction rate for children at around 95 percent.

After about an hour, we made our way out of Court No. 7 and the Ofer facility. As we were leaving, we passed the young woman we had spoken to earlier who had expressed the hope that her husband would be released the same day. She was coming out of Court No. 6 in tears. As she passed by, a group of “old hands” sitting on a nearby bench watched with a look of tired but knowing resignation on their faces.

As for the 15-year-old arrested north of Ramallah, he will eventually be released after spending three months in prison. His parents will also pay a fine of around NIS 2,000 (about 600 US dollars) and he will receive a suspended sentence and have a security file for the rest of his life. More subtle implications arising from his arrest will soon become apparent: The boy is likely to drop out of school and become distrustful and socially distant; he may show aggression toward those around him and disrespect his parents, who were unable to protect him in their home. He will also be fearful of soldiers and settlers, avoid roads near settlements, and run home if the military enters his village – and that, as the soldiers say, is the mission.

Military Court Watch is a small nonprofit organization made up of professionals from Israel, Palestine, the U.S., Europe, and Australia who share a belief in the rule of law. The bedrock of our work is the collection of evidence and advocating that, as a bare minimum, rights enshrined under Israeli military law must be respected. Over the years we have observed that Israel is not insulated from the consequences of ignoring the rule of law in the West Bank, and that cherry-picking international legal obligations is likely to harm us all in the long term.

___

Gerard Horton is a lawyer and co-founder of Military Court Watch. Gerard has worked on the issue of children detained by the Israeli military and prosecuted in military courts for the past 13 years, prior to which he practiced as a barrister at the Sydney, Australia, bar, specializing in commercial and criminal cases.

Leave A Comment