Hussein Agha and Robert Malley, Tomorrow is Yesterday: Life, Death, and the Pursuit of Peace in Israel/Palestine (Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2025).

By Peter Eisenstadt

I like to call it Eisenstadt’s Law, viz., “possible solutions for political problems tend to increase in inverse proportion to the likelihood that any of them have any likelihood of being realized.” There are situations in which possible remedies for current political difficulties proliferate precisely because none of the alternatives have a realistic chance of being achieved or implemented. If there is no obvious way forward there are only detours. For every option, it is easier to make the case for its likely failure than its probable success. For those who wish to see a just and equitable resolution, the Israel-Palestine conflict, for decades, has been a classic example of Eisenstadt’s Law.

In the aftermath, or the apparent aftermath, of the horrible Gaza War, there are, as after every war, many proposals for what to do next. Sara Roy, writing in the New York Review of Books in late October, counted 29 such plans, and no doubt their numbers have only increased since. It has always struck me as bit perverse, though certainly understandable, that in the immediate aftermath of a war, the bloodier the better, all talk turns to peace, as if the combatants have finally learned their lessons, and this war, unlike the last war or the war before that one, will at last be the war that ends all wars. Our Nebuchadnezzar, our Ozymandias said after the cease fire agreement between Israel and Hamas that the “Middle East will finally have peace after 3000 years, a very strong peace, an everlasting peace.” This will not happen. I have absolutely no brief for Hamas, but a cease-fire agreement in which one side has been creditably accused of committing genocide, though it’s the other side that is required to do the disarming, is probably not an agreement that is destined to be very long lasting. That said, we all know that in the aftermath of the Gaza War, there is no possible return to the status quo ante bellum.

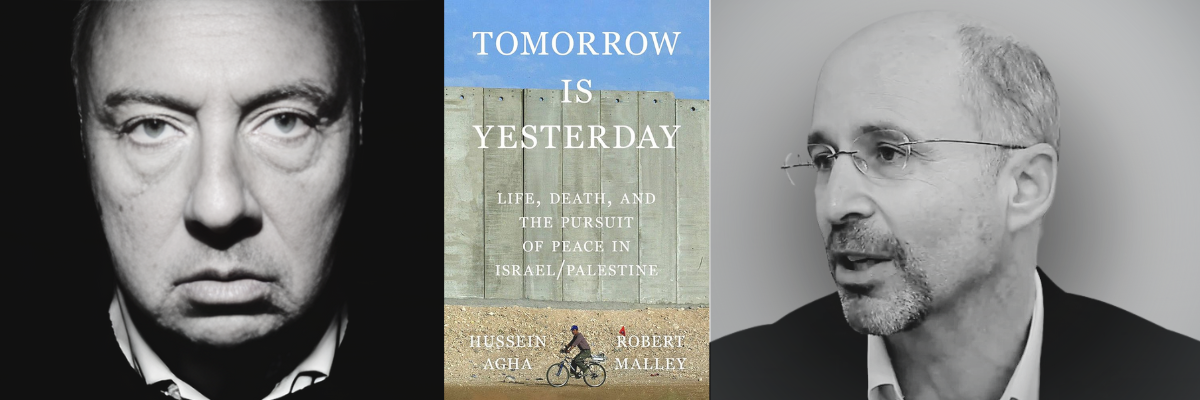

History rarely provides unambiguous lessons for the future, telling us what is to be done. Sometimes though, it can provide useful instruction on what should not to be done. In this regard, Hussein Agha and Robert Malley’s terrific new book, Tomorrow is Yesterday: Life, Death, and the Pursuit of Peace in Israel/Palestine, a history of Oslo and post-Oslo Israel–Palestine, outlines thirty years of abject and catastrophic failure. They have sterling credentials. Hussein Agha, of Lebanese background, was an informal advisor to Yasser Arafat and the PLO and taught for many years at St. Anthony’s College, Oxford. Robert Malley was an advisor on Middle East and Iranian affairs to the Clinton, Obama, and Biden administrations. This is not really one of those “in-the-room-where-it happens” books, providing a blow-by-blow history of negotiations, though it does have delicious portraits of some of the major players. Of Arafat they say he “managed to obtain his people’s trust even though they saw through his deceit and got them to swear by him even though as they knew full well he was a liar and a cheat.” But it was his genius, if you want to call it that, that he “was able to transform the two-state solution from an act of betrayal and high treason to what most of his people for a time came to see as the pinnacle of their national struggle.” And they also interacted with Ehud Barak at Taba, with his “generous view of himself and resolve to quiet any hint of blame” for any of his actions.

But as I said, the book is not really about personalities. The main problem with post-Oslo talks was not the negotiators, but what the negotiations were attempting to achieve. After the recent ceasefire was announced, Agha and Malley were asked about the future of Israel and Palestine by Ezra Klein in the New York Times. Malley replied:

The best advice, I guess, is what you’re referring to, which is what not to do and not to replicate the ways of the past—which I think they’re unlikely to do in any event — but not to simply decide, as we see some people doing, jumping to the next shiny object, which is: Let’s try to revive the two-state solution. Let’s try to revive negotiations between the two sides.

It hasn’t worked, and it hasn’t worked for 30 years under much, much more auspicious circumstances than we see today. So we have to discard all of the formulas, all of the plans that people may come up with, however tempting they may be. And, in the case of the two-state solution and the pursuit of peace, it’s not a couple of mishaps. It’s decade after decade after decade—not just of mishap but of failures that have led to the catastrophe, the horrors of Oct. 7, and of what followed.

Tomorrow is Yesterday is an extended argument against the two-state solution, which has been the goal of every US administration since Carter, though the words weren’t officially used till 2002, which was one of the problems. The argument goes something like this. There are two peoples on the land of historic Palestine. They obviously despise one another. The only sensible thing to do is to divide the land, and send the squabbling parties to their respective corners. Its advocates think it the only plausible way forward, and anyone who challenges it is illogical, either a quixotic utopian or an overemotional partisan of one side or another. If administered fairly, with a strong hand, everyone will come to see the wisdom in doing this.

Agha and Malley are not that interested in some of the obvious arguments against two states. There is no clear place to put a Palestinian state, with Gaza a rubble-strewn charnel house and newly partitioned, and the West Bank a settler-infested battle ground. Partitions, when the enmity is great, almost never work, with Ireland, India, and the UN’s partition plan for Palestine as examples. Almost all versions of the two-state solution have a built-in pro-Israel bias, in which Palestinians have to foreswear most of historic Palestine, and Israel would only have to discard part of their gains from 1967—easier said than done, I know—and could remain a Jewish state. No, their objections to the two-state solution are more fundamental. Neither Israelis nor Palestinians like it, want it, nor are willing to sacrifice to see it realized. It is a cartographic solution, viewing the Israel-Palestine conflict simply “as a territorial spat, the challenge as one of drawing lines on a map. This did not reflect the reality, feelings, and yearnings of all those upon whom this construct was imposed.” It ignores history and its resonances. “Israelis want genuine acceptance and normalcy,” and permanent security. Palestinians want “justice, redemption and dignity” and freedom from Israeli domination, and the two-state solution grants neither side what they really want.

Agha told Klein why, though they support the idea of Palestinian sovereignty, the two state solution, as it is usually conceived, is unworkable

The first thing you have to do is you have to completely forget about reason and rationality when you deal with this region. The Western ways of doing things do not hold, and they have no resonance among the inhabitants of this part of the world.

It’s messy, and you have to be ready for this messiness by not trying to straitjacket it into neat resolutions because the resolutions are neat in your mind. In the nature of the reality of this region, you have to look for clarity in the confusion and not deny the confusion and not believe that there are simple quick fixes to the problem you are facing.

Agha writes that he often found that those on the Israeli left, two-state solution backers, “tended to celebrate fictitious Palestinians whom they imagined content at the thought of recovering 22 percent [of Mandatory Palestine], giving up the rights of refugees, ready to bury the 1948 conflict for the sake of addressing the consequences of the 1967 war.” For him, “along with many Palestinians, what the Left considered praise was indistinguishable from contempt, a belittling of their national cause. They appeared arrogant, condescending, a touch racist.” That is, “they know what is good for them. They know what is good for you…there is nothing left for you to do but to agree and accept their prescriptions.” Instead he had a “predilection for dealing with right-wing Israelis, whom he found more genuine in their attachment to the land, and, therefore, in what is not a paradox, more understanding of the Palestinians’ similar feeling.” They knew a line on a map was incapable of changing the connection of either people to their land. They understood the deep emotional connection of both peoples to the land.

Palestinian and Israeli emotions are at the heart of Agha and Malley’s book. It is not that they are irrational, but that they create their own structures of rationality. Tomorrow is Yesterday does not consider this, but the study of the history of emotions has been subject of considerable interest to historians in recent decades. Barbara Rosenwein has popularized the idea of “emotional communities,” the idea that all communities are in part held together by the emotions they encourage and the emotions they discourage, and that this changes over time. One recent work much influenced by Rosenwein and the history of emotions scholarship is Derek Penslar’s recent excellent history of Zionism, Zionism: An Emotional State, which analyzes it from the perspective of its emotional resonances and transformations. Surely, in its earliest phases Zionism was little more than an emotion in search of a homeland. Penslar traces the emotional evolution of Zionism from Herzl to Netanyahu. Israel and Palestine have distinct emotional communities comprised of many contending emotional sub-communities. The question of how October 7 and the Gaza War have changed the emotional realities of Israel and Palestine is a topic that should interest us all. For some Israelis the Gaza War has intensified emotions of guilt, shame, and anger at Israeli conduct; for others it has magnified an underlying hatred of Palestinians. Among Palestinians there is a similar emotional bifurcation with complex attitudes to Hamas, and hatred of Israel is mingled with a desperate search for a normal life.

For Agha and Malley, the two-state solution ignores, violates, and exacerbates the emotional realities and hostilities of both peoples. “Deep down most Palestinians, though ready to accept Israel’s existence, have not accepted its historical legitimacy, and though supportive of cease-fires and peace agreements, they have not relinquished the right to fight for their land or to return to it.” The right of return remains central to Palestinian aspirations for the future. For Palestinians any state that does not include the right to return to the land they lost in 1948 would always be just a stopgap, an intermediate and impermanent solution. But Israel would view any creation of a Palestinian state with its powers and boundaries as final, an ultimate, maximum concession, though Palestinians would treat everything about the new state as merely provisional, and would continue to push for a better deal in the future. No one would be satisfied. And a weak, demilitarized Palestinian state, rather than bringing stability, is a recipe for perpetual war of one sort of another. (Perhaps the best way for a Palestinian state to have something approaching a stable, if frozen, peace with Israel would be if Israel gave the new Palestinian state half of its nuclear arsenal.) Short of this impossible-to-happen circumstance, the strength of Israel and the weakness of any Palestinian state will always undermine the stability of any arrangement between them.

The arguments against a two-state solution in Tomorrow is Yesterday are extremely persuasive. However, the book does not avoid a corollary to Eisenstadt’s Law, namely, that the last chapter of any book on the Israel-Palestine conflict is almost always the weakest, because in the final chapter, after analyzing current problems and criticizing other ideas on how to deal with the situation, the authors finally have to get around to presenting their solutions. And like everybody else’s ideas, they come up short. Agha and Malley’s suggestions, offered with appropriate caution and reservation, include decentralization with greater opportunities for Palestinian self-government within Israel’s overall control, a Jordanian-Palestinian confederation, Palestinian-Israeli confederation, and bi-nationalism; all ideas that have been suggested in the past, and all of which have their plusses and minuses. Compared to them, the two-state solution is no more implausible than these suggestions. There has never been a time since 1948 when Jewish/Palestinian cooperation seemed more unlikely and more likely to fail, when both peoples want, more than anything else, some sort of separation. Two states is the worst possible future for Israel and Palestine, except perhaps for all the others.

And perhaps the real target of Agha and Malley is not the two-state solution as such, but what might be called solutionism; the idea that somehow, somewhere, there is a neatly wrapped solution waiting to be discovered, if only persons of wisdom really put on their thinking caps. Perhaps egged on by a glory-whoring American president seeking improbable reinvention as a peacemaker, there can be a resolution of the conflict that can be found in a conference, a boundary, or an agreement. But from messy emotions come messy solutions. In the words of Immanuel Kant, out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made. Or in the words of the late Dusty Springfield, all those who wish to see a better world for Israel and Palestine must partake in the politics of “wishin’ and hopin’ and thinkin’ and prayin’ and plannin’ and dreamin’.”

Agha and Malley suggest that the messy way forward is to pay close attention to the overlapping emotional communities of Israelis and Palestinians. Let them jointly agree to try to tackle the most stubborn and powerful emotion of them all, fear, and its close relative, hate. In an adversarial relationship, the best way to reduce your own fear is to address the fears of your adversary. Perhaps there can be, somewhere on the far distant horizon, a Grand Bargain in which Israelis recognize that what Palestinians want most is not to be excluded from their homeland, along with fear of Israeli domination and arbitrary treatment, and what Israelis want is real security, leading to some sort of confederation; that is, to work with, and not against the basic emotional needs of both peoples. People and peoples can grow only if their essential emotional structures are respected.

Tomorrow is Yesterday has a number of apt and unhackneyed epigraphs for its chapters. Let me close with two of them. Perhaps someday both peoples will recognize that in the words of the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa, “the feelings that hurt the most, the emotions that sting most, are those that are absurd, the longing for impossible things.” And if they acknowledge impossible emotions, perhaps they will allow themselves to find a future unconstrained by artificial boundaries or restraints, and finally refute Eisenstadt’s Law. This will have to be a new kind of story or narrative, perhaps like the story suggested by the great director, Jean-Luc Godard. “A story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end, but not necessarily in that order.”

Peter Eisenstadt is a member of the board of Partners for Progressive Israel and the author of Against the Hounds of Hell: A Biography of Howard Thurman (University of Virginia, 2021).

Footnotes:

- Sara Roy, “What ‘Day After’ for Gaza?” New York Review of Books, 25 October, 2025.

- Ezra Klein, “Two Middle East Negotiators Assess Trump’s Israel-Hamas Deal,” New York Times, 17 October, 2025.

- For an overview of the idea of emotional communities, see Barbara H. Rosenwein, Emotional Communities in the Early Middle Ages (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006), 1–31.

- Derek Penslar, Zionism: An Emotional State (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2023)

Leave A Comment