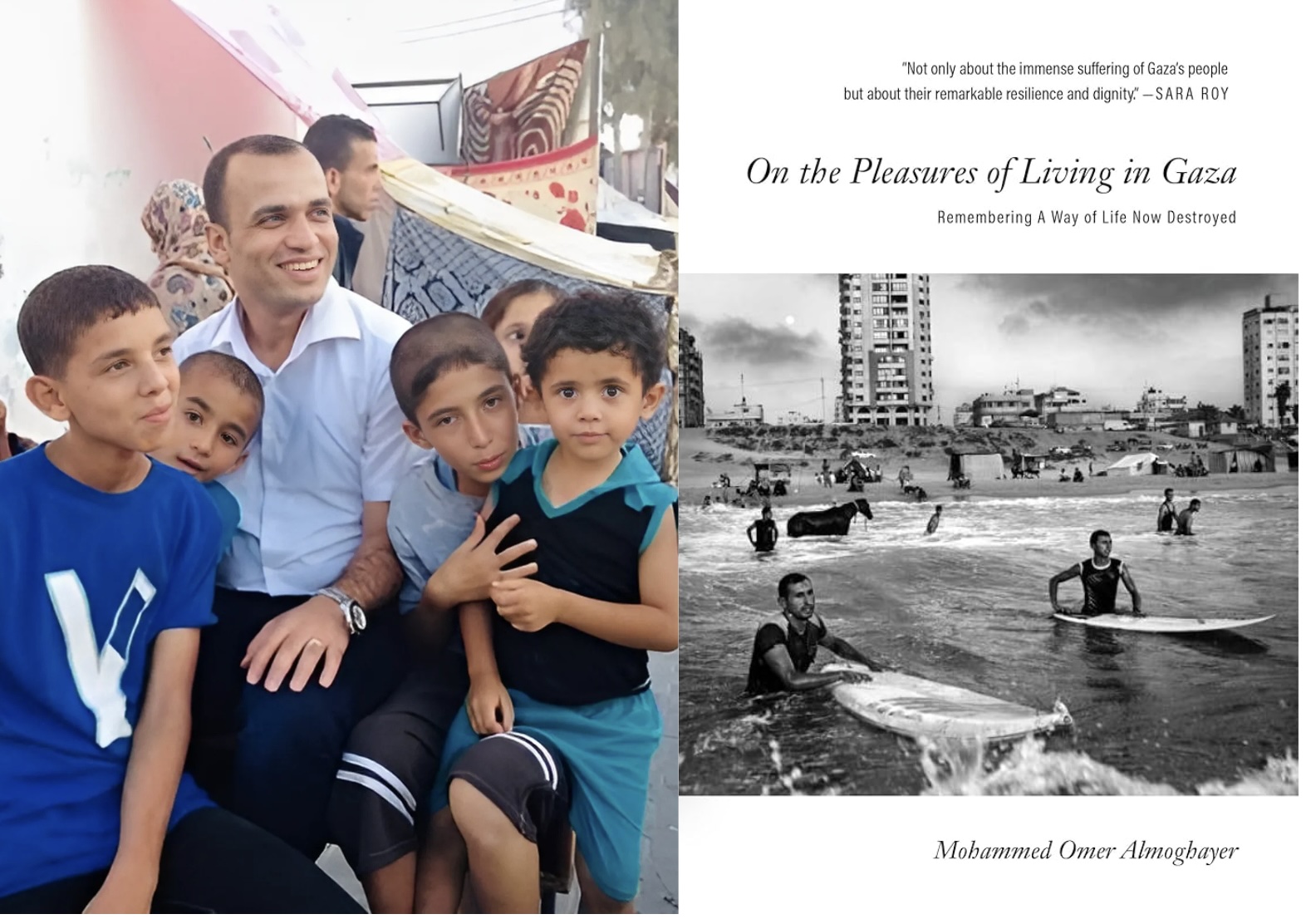

Mohammed Omar Almoghayer, On the Pleasures of Living in Gaza: Remembering a Way of Life Now Destroyed (New York: OR Books, 2025):

By Rabbi Margo Hughes-Robinson

A few hours before Shavuot, I found myself half-shouting into my laptop in a New York City park as I attempted, derailed by a subway interruption, to teach a class on literary works from Gaza. My extremely forgiving Shavuot tikkun students delved into classical Hebrew works by the rabbi-poet Yisrael Najara alongside Arabic poems in translation by the likes of Basman Aldirawi. In the middle of the session, I introduced an excerpt of journalist Mohammed Omer Aloghayer’s just-published new work, On the Pleasures of Living in Gaza.

The group assembled online for this virtual class had ostensibly already long been involved in the international movement for a ceasefire in Gaza, so I was struck by the responses that even a few lines of the book generated. One participant remarked that it was striking just to encounter even a few paragraphs reflecting on the lives of Palestinians in Gaza that did not focus on the impact of the ongoing bombings, shootings, and starvation that now characterize life in the enclave; to instead read a celebration of the warmly quotidian: particular homemade dishes, a group search for a lost cellphone, even just admiration for the Mediterranean sea and Gaza’s beaches. In the waning hours before Shavuot, standing face to face with a living Palestinian culture felt like revelation.

Almoghayer was born and raised in Rafah, two years after the city was split in half between Egypt and Gaza as a result of late 1970s peace talks between the latter and Israel. In the introduction to Pleasures, he notes that he signed the contract to write the book several months before Hamas’s attack on Israel on October 7th, 2023 and the subsequent war that has reduced much of the enclave to rubble, but still chose to write his work “in the present tense to make Gaza feel alive once more – an illusion, a resurrection, a magic spell. A chance for [the reader] to feel, as so many of us have, to see it all before you… and then to wake up from the dream and see it laid to waste.”

While some readers may be familiar with Almoghayer’s work from his bylines in outlets including the New York Times and the Nation, or his academic career in the field of sustainability and interventional development, On the Pleasures of Living in Gaza is not a work of political analysis or a discussion of statecraft. Instead, Pleasures is a paean to a world that was destroyed as its author labored to record it, an homage to the resilience of a life made beautiful in defiance of successive wars and two decades of military blockade.

Chapters that serve as snapshots of Gazan individuals and micro-communities in full bloom – teenagers whose parkour practice creates an opportunity for sport amidst ruined buildings, a growing counterculture of dog lovers who arrange in-person meetups via social media, a NASA scientist who returns home to Gaza from Virginia after the death of his son in a missile strike and uses his diplomatic relationships to arrange delivery of educational telescopes for young science students in the enclave – are interspersed with a running narrative of Amloghayer’s attempt to locate a Palestinian man named Naji living in the periphery zone of Gaza’s northern border with Israel.

Naji is the subject of a shocking photograph (in a thoughtful and sensitive gesture, the image is not included in the book, only described) where he is half-buried in the ground while an IDF soldier from the “buffer zone” in which Naji lives points a gun in his direction. The image, we learn, was seen by an American family in Houston who wishes to find Naji and his family and financially sponsor them; Aloghayer’s efforts to identify a previously anonymous Naji from the photograph and connect him to his foreign benefactors, substantially changing his family’s circumstances, provide a running narrative woven amidst the short portraits of Gazan citizens portrayed in each chapter.

Since its publication only a few months ago, On the Pleasures of Living in Gaza has received considerable pushback from readers and reviewers: many have noted that its depictions of Almoghayer’s neighbors can scan as overly “rosy,” or even flat in their optimism. And Pleasures does bring a perspective that runs counter to much of the discussion with and about the Gazan experience that many readers of this publication – or more broadly, within a policy-focused worldview and conversational bubble – may find wanting if they greet the text with expectations of engaging with broad political history. Amidst the pages of Pleasures, history exists as it interrupts the personal: families separated by the wall splitting Rafah along the Egyptian and Gazan shared border, a local farmer’s unique identity and pride in living on land that her family worked and owned prior to 1948. Almoghayer’s book does not discuss governing structures or the reality of Hamas administration in Gaza, and Israel appears as a source of rockets, blockade, and soldiers along borders maintaining deadly buffer zones. The hope for a free Gaza and Palestine is frequently expressed, but the political shape of that freedom is not detailed. The larger political catastrophes that have shaped life in the region hold the same place in the book that they might in a conversation with one’s neighbor at the local pharmacy: present, but as background information to the life happening here and now.

There is also extant criticism that may accompany any narrative that seeks to “humanize” Palestinians in Gaza. Almoghayer’s colleague at the Nation, Mohammed El-Kurd, frames this argument in his own recently-published essay collection Perfect Victims and the Politics of Appeal (Haymarket, 2025). While my own commitment to nonviolent action necessitates a deep disagreement with the thrust of El-Kurd’s book, his point that any work that pushes back on Israeli and international dehumanization of Palestinians does, in some way, accept the premise and reify the discrimination baked into this kind of response does ring true. There is a brittle sadness that accompanies Pleasures, in that the dignity of the individuals and communities profiled underscores the level of degradation to which they have been subjected.

In its emotional resonance, Pleasures can bring to mind David Teitelbaum’s films depicting his hometown of Wielopole, Poland. In the late 1930s, Jewish-American businessman Teitelbaum returned to the shtetl where he had been raised, creating amateur color film recordings of his remaining family and former neighbors, unaware of the destruction and mass murder that awaited the community only a few years later at the hands of the Nazis. With his Dutch passport, Almoghayer has both an ability to travel in and out of the enclave and even avoid kidnapping by ISIL affiliates – as depicted in one of the book’s final chapters, as the author reflects on a jarring incident from 2015 where he was detained for two days by militants associated with the Islamic State, which Almoghayer refers to as “the dark side.” Like Teitelbaum, Almoghayer’s experience of his home is at once intimate and removed; he curates the experience for his readers even as he invites them into intimacy with the neighborhoods and experiences that raised him.

A layer of cold horror pervades the work, made explicit in the book’s epilogue. Often while reading On the Pleasures of Living in Gaza, I found myself pausing to research and read more online or elsewhere about the work of an artist or scientist profiled in the book, and then encountering their personal experiences of the catastrophic conditions in Gaza: Fashion designer Nermine Demyati’s Instagram no longer showcases her designs but instead her attempts to continue to feed her small children in the face of repeated forced evacuations. Young artist and community educator Mohammed Qriaque was killed in the Al-Ahli Hospital explosion in mid-October 2023. We do not find out whether or not Naji’s family has survived.

Ultimately, what Almoghayer asks his reader for is not understanding, but witness – a recognition that the people he writes about are not statistics; rather, they are whole universes unto themselves. The insistence here is upon recognizing Palestinians as people, not as numbers or stereotypes of “terrorists” or even as perpetual, flat victims. Palestinian lives are not here for Western witnesses to somehow make meaning of, not unlike the grand tradition of Augustinian flattening of Jewish civilization into an unwilling “witness” to a Christian narrative of history. There is a kind of zombification of Palestinian experience across the political spectrum, where the lives lived in Gaza are not whole and complex but instead flattened into their “usefulness” for a political point. What Pleasures asks of its readers is an embrace not of complexity, but of human lives lived as they are. The loss in Gaza, he insists, is not only amongst the Palestinian people, but is part of a world that allows it to happen and is being scarred by that permission; “a system that allows tens of thousands of innocent children to be intentionally starved, maimed, killed, and orphaned while the world watches.”

As he writes in the epilogue,

“No one in this world understands what it’s like to die so silently, this glaring identity loss, the fact that we are susceptible to erasure with such offhand ease and audacity. It’s not possible to understand this rare kind of grief without experiencing it firsthand. We don’t blame those who don’t share this sorrow with us, only those who refuse to see it.”

Certainly, I could not recommend On the Pleasures of Living in Gaza as the only book that one should read right now about Palestinians and their perspectives and experiences. But even more so, I could not recommend that anyone read only a single book, or encounter only one angle or voice from amidst the Palestinian experience. Pleasures is an open door to the multivocality of everyday life in Gaza as it was, an invitation to a world we have all become complicit in destroying.

Rabbi Margo Hughes-Robinson is the Executive Director of Partners for Progressive Israel.

Leave A Comment