PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

Looking Ahead to Israel’s 2026 Elections

By Paul Scham

December 2025

By law, Israeli elections must be held by November 2026, a year out as I write this message. These elections will be deeply consequential for both Israelis and Palestinians, and I want to offer as a primer a review of the legal background and recent history, and then plunge into what current polls can tell us about the potential outcomes and pitfalls of the upcoming votes.

Note: I will be commenting on Israeli politics regularly, so if you’re interested, you can become a free subscriber to my Substack, “Israel and its Neighbors.” Questions and comments are welcome, in the free-wheeling spirit of Israeli politics

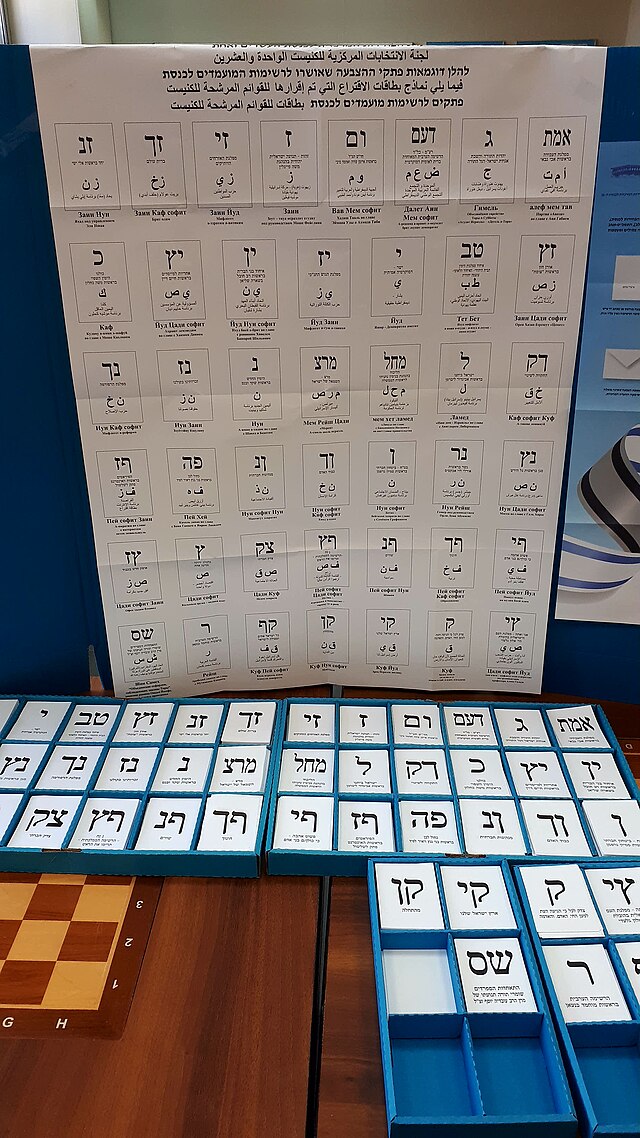

Keep in mind: Israel has a typical European-style parliamentary system. Normally, between 20 and 30 parties compete and around 10 usually exceed the threshold of 3.25% of the vote and actual get into the Knesset. There is fairly strict proportional representation, so 3.25% gets you 4 Knesset seats. No party has ever won a majority of seats; thus, every government has been a coalition.

A Brief History

From the 1960s till the 2000’s, Israel’s two larger parties, Likud (center-right) and Labor (center-left), each usually received 30-40 seats (mandates) in elections held every 3-4 years. About a third of the total of 120 seats were held by 6-10 smaller parties, with several of whom one of the larger two parties formed a coalition, except when the two large parties created “National Unity “ governments during the 1980s (often derided as “national disunity”). After the failure of the Oslo peace process in the 1990’s, Labor gradually declined into insignificance, and the Likud was generally the single largest party. For those seeking a general guide to current parties, I recommend Wikipedia’s chart. Keep in mind that parties, candidates, and even rules will change, perhaps abruptly, over the coming year.

Traditionally, Israeli parties were fairly clearly left, right, or (Jewish) religious. Starting in the 1980s, independent Arab parties began to appear – understood to be beyond the understood Jewish-Zionist consensus – and which were not invited into coalitions. Traditionally the leftwing parties always included Israeli Palestinians in their slates.

Bibi’s coalitions after 2009 generally included some combination of center-right, right, and religious parties, both national religious (pro-settler) and Haredim (“ultra-Orthodox”). However, by the 2015 election, and certainly by 2019, Israelis parties had morphed into pro- and anti- Bibi Netanyahu blocs, almost regardless of ideology, Many of the anti-Bibi parties were led by former Bibi coalition partners (e.g., Lieberman, Bennett, Shaked, Gantz, and Lapid), who swore they would no longer work with him. Each grouping, pro- and anti-, had almost exactly 50% of the electorate, and four inconclusive elections were held between 2019 and 2021, with no one gaining a clear majority, except for a brief anti-Bibi “Government of Change” in 2021-22. Then, in November 2022, Meretz fell a few thousand votes below the threshold and its 4 seats disappeared. Bibi formed a government, still in power, with 64 seats, now increased to 67.

There are some unusual features of the current government which must be understood for the last three years to be comprehensible. Normally, one of the inherent characteristics of a coalition government is that moderately different viewpoints and priorities are represented by the different parties, so extremism is usually curbed and moderation is prioritized. However, due to the unprecedentedly long tenure of one person as prime minister – and especially of the five pro- and anti-Bibi elections in 2019-22 – Likud had become as subservient to Bibi as Republicans are to Trump. Meanwhile the Haredi parties became politically wedded to Bibi, and knew that the anti-Bibi parties would never let them into a different government, largely because of their insistence on military exemptions for virtually all Haredi draft-age men.

Meanwhile, Bibi had been indicted for fraud, bribery, and breach of trust. Due to a quirk in Israeli law, the PM, unlike other ministers, is not obliged to resign if indicted for a crime and, though his trial has been ongoing for 5 years, he has been able to slow it down considerably. If his government falls, however, Bibi may soon go to jail. The far-right party leaders Ben-Gvir and Smotrich, now household names, have not hesitated to use implicit and explicit threats of leaving the government in order to implement their own unprecedentedly far right agenda, including, among many other items, prosecuting the savage war in Gaza for two years and encouraging extreme settler violence in the West Bank, often ensuring police inaction or even participation. Bibi himself, who had previously taken a mainstream right wing approach to Palestinian issues (e.g., strong opposition to a Palestinian state but also to Israeli annexation of the occupied territories), at first appeared reluctant to accede to their policies but, in the last year, has appeared far more aboard with them, even enthusiastic.

The Current Situation (I should note that I get my up-to-date polling information from https://knessetjeremy.com, (unconnected to PPI or me), who provides a regular (usually weekly) summary of Israeli polls, in English.)

Keep in mind that the size of a post-election coalition determines who “wins” an election, not the vote for an individual party. Making the Israeli pollster’s job excruciating is having to game out which politicians may run in which party, how many votes each party might garner, and who is likely to join a potential governmental coalition. At this point, most assume that Naftali Bennett, prime minister for most of the 2021-22 “Government of Change” will lead a new party and create the largest anti-Bibi coalition. Bennett’s politics are nominally of the settler far-right, but his apparent flexibility and willingness to work with centrists and even the “liberal Zionist” Demokratim, make him appealing to the broadest array of voters and parties. Polls show his registered but as yet unnamed party just a few seats behind Likud. Meanwhile, Likud is trying to derail it, as one would expect.

Though Bibi’s negative ratings have exceeded his positives since 2017, his base support is only slightly lower than it was in the 2022 election (32 seats then; upper twenties now in most polls). If you are looking at KnessetJeremy’s chart, you will note that Channel 14’s numbers are out of line with the others, skewed in Bibi’s favor. Chanel 14 is known as Israel’s Newsmax, rightwing and pro-Bibi in everything.

Bibi’s coalition, should he be able to form one, would consist of Likud, the Haredi parties United Torah Judaism (Ashkenazi) and Shas (Sephardi/Mizrahi) and the two far right religious parties Otzma Yehudi (Jewish Power), led by Ben-Gvir, and Religious Zionism (now a party as well as a category), led by Smotrich. The two men apparently dislike each other so strongly that they refuse to run together in one party, although their views are similar, though not identical. Smotrich’s party hovers below the threshold; only Channel 14 shows him barely entering the Knesset. In 2022 Bibi essentially forced them to run together and they won an unprecedented 14 seats, providing the power they now have. That seems less likely to happen next year, which would make it difficult for the pro-Bibi forces to reach the magic number of 61 out of 120 seats.

As Knesset Jeremy shows, the “Bennett bloc” is likely to end up in the upper 50s, and the Bibi bloc in the lower 50’s or upper 40s.

What gives? There are 120 seats in the Knesset!

The “missing” mandates are held by those who do not accept the Zionist consensus that still loosely connects the Israeli right and left. Most of those not accepting the consensus are Israeli Arabs/Palestinians; those with Israeli citizenship, who comprise 20% of the Israeli population. There is also a group that is willing to accept the consensus, but is not accepted by it.

In my next post in this series on the Israeli elections and political system, I’ll discuss the anti-Bibi portion of the Knesset and the likely potent role of Israeli Arabs.

Paul Scham is President of Partners for Progressive Israel and Director of the Gildenhorn Institute for Israel Studies at the University of Maryland, where he is a Professor of Israel Studies.